Should foreign tourists leave Zimbabwe? At this moment no foreign embassy issued travel warnings against Zimbabwe. However tweets observed say, the recent campaign by tourism officials announcing Zimbabwe is open for business and tourism” might have died a premature death/

After a violent crackdown in Harare and other regions Tuesday night, a scary calm is returning to portions of Zimbabwe.

At the same time, tweets received from Victoria Falls say:” Clearly these so-called election observers came for tourism! Tourism in this northern Zimbabwe resort town seems to function normally. Hotels are booked, tours selling out and posters invite to fun events.

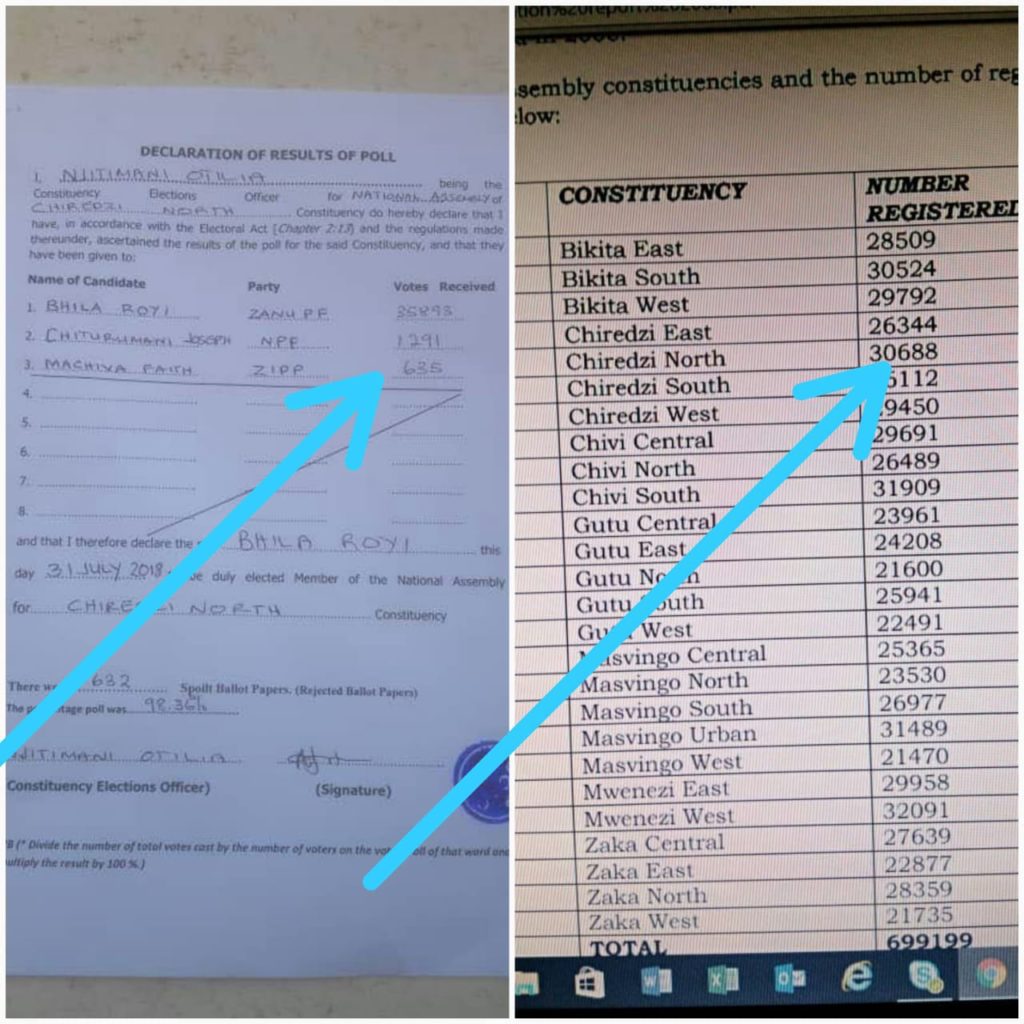

In Harare some election documens show almost impossible results. This voting paper (see picture) shows 30688 registered voters in Chiredzi North.

The declaration of the result of the poll show, however, a lot more votes than registered citizens. In addition, numerous papers show ZANU P.F. received all votes, and zero votes for all other candidates what is practically impossible. The current president put in power by the military overturn is from the ZANU P. F. party.

The UN and Europe were fooled into accepting the Zimbabwe regime which was organically a military takeover of government in November 2017.

This regime is accused of rigging elections and brutalizing citizens who peacefully expressing their dissatisfaction.

Heavy-handedness, killings of unarmed people including indusindustriale injuring of innocent unarmed people requires UN intervention on the basis of the responsibility to protect.”, a Zimbabwe citizen said on social media.

Zimbabwe, if not kept under control could become another 1994 Rwanda in the making.

The UN must take action now and deal with unprofessional command element of the Zimbabwe military. In fact the entire command structure of the Zimbabwe military has remained fundamentally violent right from the time of the war.

38 years after the war, their hold on to the security cluster is tight. Also, the archman of former President Mugabe was Mnangagwa now who came into office by military means. He has managed to bambazoole the entire EU.

The United Nations with the exception of US had adopted a cautious approach on Harare. The regime in Zimbabwe must be held accountable now.

The military intefered with election results. The opposition won the election but this will never be official.

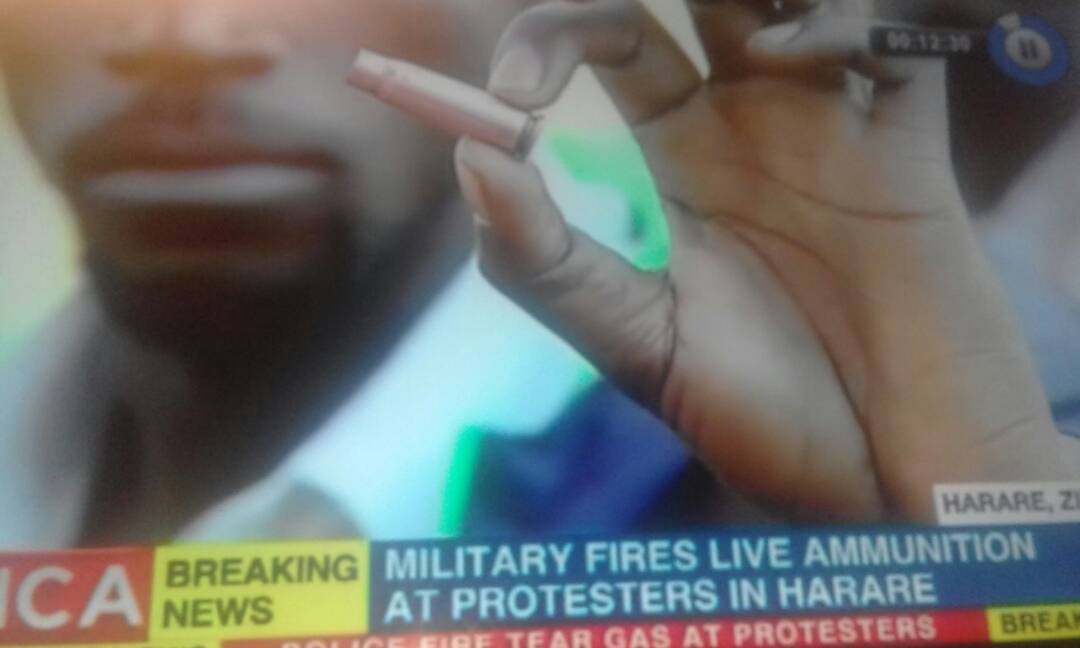

The government crackdown in Zimbabwe after Monday’s elections has prompted international calls for restraint.

The UN and former colonial power the UK both expressed concern about the violence, in which three people were killed after troops opened fire.

Parliamentary results gave victory to the ruling Zanu-PF party in the first vote since the removal of former ruler Robert Mugabe. However, the opposition says Zanu-PF rigged the election.

The result of the presidential election has yet to be declared. The MDC opposition alliance insists its candidate, Nelson Chamisa, beat the incumbent President Emmerson Mnangagwa.

UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres urged Zimbabwe’s politicians to exercise restraint, while UK foreign office minister Harriett Baldwin said she was “deeply concerned” by the violence.

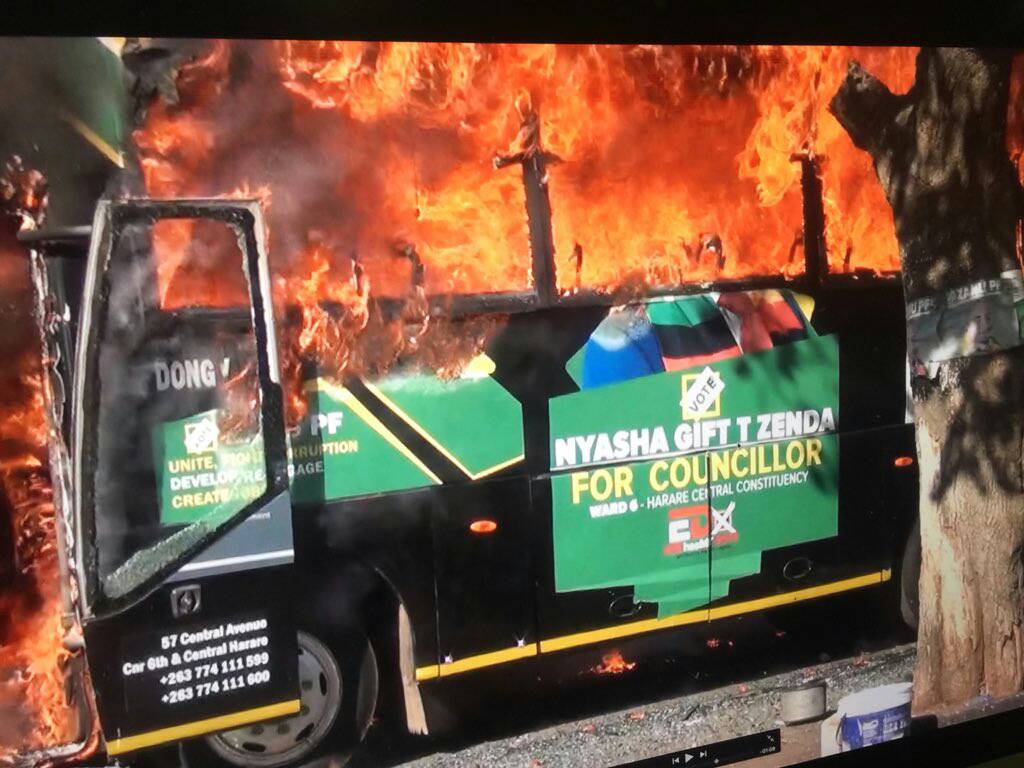

These pictures and videos need no explanation:

The movement for democratic change already smells a rat. Mugabe stole elections. They are not going to let that happen this time and they are convinced the results were rigged.

This is now an extremely dangerous situation. In Harare yesterday protesters caught by the army were severely beaten, this scene hauntingly reminiscent of the violence that characterized Mugabe’s despotic rule.

As the afternoon yesterday wore on, the crackle of automatic fire could be heard sporadically across the city. Riot police fired tear gas and soldiers were deployed as armored personnel carriers and water cannon cruised the streets, and an army helicopter kept watch from above.

Last night, streets of this capital had been emptied. It’s spookily quiet, and it’s tense. No word from either presidential contender, other than on Twitter. Nelson Chamisa, the challenger, still claiming victory. Emmerson Mnangagwa, the incumbent, calling, ironically, for everyone to act peacefully.

The results will be announced today. Protests will eventually continue today. This is the overall opinion of insiders.

Risk of military intervention:

“The response from the military in opening fire on MDC Alliance protesters in the streets is fast undermining the goodwill that Mnangagwa has built in recent months from the international community. While the protests were triggered by MDC politicians led by Nelson Chamisa repeatedly – and illegally – declaring victory before the official results, the unmeasured military response bears witness to a security apparatus little reformed since the Mugabe era. It matters little whether this heavy-handed response came on Mnangagwa’s orders: evidence that the president lacks the authority to control the security forces will be just as damning in terms of the impact on Zimbabwe’s international rehabilitation. Risks related to military involvement in politics and the quality and responsiveness of political institutions will remain a concern in Zimbabwe.”

Christopher McKee, CEO of PRS Group issued a risk report on Zimbabwe . It says.

Risk of the election impacting international financial assistance:

“A constructive international response to this election is desperately important for Zimbabwe’s new government because, without substantial external financial assistance, there will be little basis for undertaking a serious program of currency reform and as long as the country is hobbled by continued sanctions, it will remain isolated and strapped for cash – conditions that are hardly conducive to creating a more hospitable climate for investment.

“Zimbabwe’s political risk score had improved from ‘very high risk’ at 48 last August to ‘high risk’ at 54 before the elections, within a range that ranks Sudan at 37.5 and Norway at 89.5. Political risk had been easing as parts of the international community prepared for a new Zimbabwe in the post-Mugabe era, improving the outlook for government stability and foreign relations. The pace of this support – given what we’ve seen following the vote in terms of the violence – is likely to be slower as the international community reassesses. Crucially, the EU has given a mixed assessment, noting examples of soft coercion and bias from state institutions in ZANU-PF’s favour. Such concerns will only deepen the more that the presidential election results are delayed and should the violence escalate further. It is incumbent on the current government to act judiciously in handling the MDC Alliance’s protests against what the opposition claims is widespread fraud, as the response will undoubtedly influence international opinion as to whether Mnangagwa’s commitment to democratic reform is genuine.”

Risks after the election announcement:

“Zimbabwe’s financial risk profile is among the worst in Africa at 35, only slightly above the regional low of 30 for Ethiopia and compared with 47 for Botswana. Even if the immediate post-election unrest quickly dies down and Mnangagwa is sworn into office, the risks for investors will remain high. For all his talk of reform, Mnangagwa stuck pretty closely to the Mugabe playbook throughout his campaign. He raised the salaries of 350,000 state workers by an unaffordable 15%, and increased benefits for war veterans – two constituencies that historically were the bedrock of Mugabe’s autocratic rule, and can be expected to use their leverage to influence the government’s policy agenda. Tellingly, while Mnangagwa has spoken of compensating white farmers whose land was seized under Mugabe, he has unequivocally ruled out white ownership of farmland, a stance that likely has unfavourable implications for mine owners hoping for abandonment of the so-called ‘indigenization’ law.

“In terms of overall policy and effective governance, the prospect of a victory for Mnangagwa and ZANU-PF had been viewed through our data and by the financial markets somewhat more favourably than a win for the opposition. Investors seemed prepared to give Mnangagwa the benefit of the doubt in view of his expressed willingness to implement liberal reforms. Yet confidence on that score assumes that a ZANU-PF government formed after the elections will be able to count on support from multilateral lenders and the international donor community.”

WHAT TO TAKE AWAY FROM THIS ARTICLE:

- In fact the entire command structure of the Zimbabwe military has remained fundamentally violent right from the time of the war.

- The current president put in power by the military overturn is from the ZANU P.

- After a violent crackdown in Harare and other regions Tuesday night, a scary calm is returning to portions of Zimbabwe.